How To Cope With Death Every Day in Somalia

Now for another chapter from my new, as yet unpublished manuscript. It concerns the end of my first assignment as a U.N. Peacekeeper in Somalia, one of my most dangerous assignments. Death was all too common and you had to learn to deal with it.

Coping With Death

After witnessing the student’s death, any reluctance I harbored about leaving Somalia left me. A short-timer syndrome set in. I first heard of the syndrome from friends of mine who had done a combat tour in Vietnam. It referred to the premonition that with only weeks to go before their tour ended, they became convinced they would get killed before they had a chance to board the flight home.

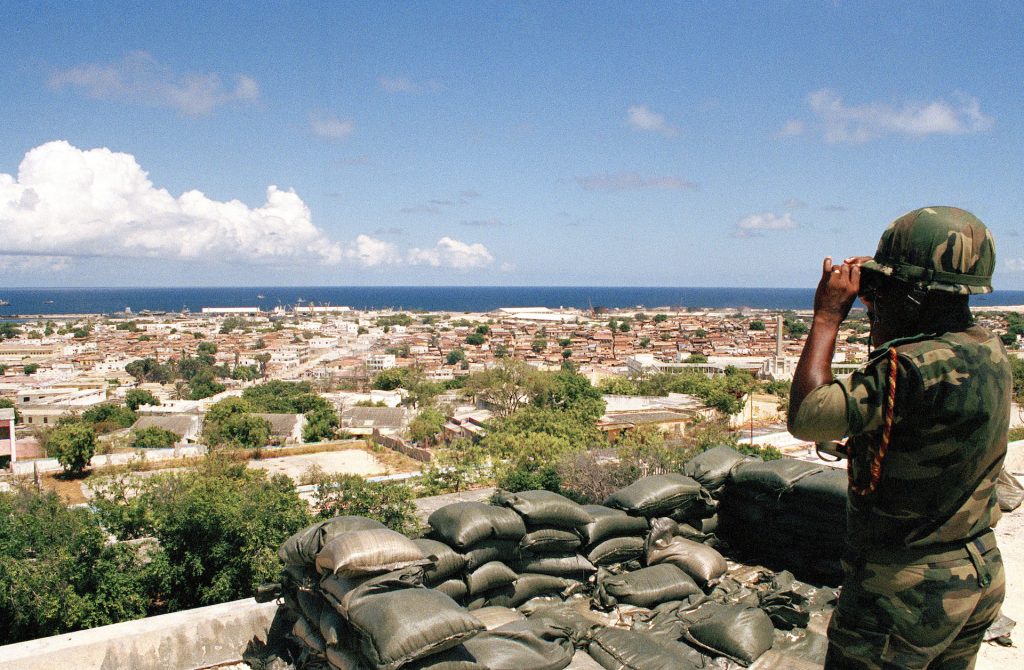

The image of that boy’s skull exploding against a wall kept surfacing in my mind. Even though I refused to dwell on it, I purposely avoided open spaces where I could be exposed to snipers. I didn’t go to the open rooftop regularly like I used to. I often wondered if I had just been lucky to never have been hit by a stray bullet. I began to fear the odds could turn against me at any moment.

I busied myself packing, writing my handover notes, and attending parties. The staff turnover in Somalia was so great, it didn’t surprise me there was no special celebration for those leaving the mission, complete with a lot of beer and wine, a little roasting of the person leaving, and maybe a group photo or plaque.

With people coming and going at such a high rate, it would have been impossible to keep up. Before I left, I made a point of having drinks with close friends at one of the several canteens around the compound and said my goodbyes.

My last full day in the office, I turned my notes into Alesia. That night in bed, I thought through all the departure details for the next morning until I fell asleep. One more day and I’d be out of here alive.

Leaving Somalia

Departure day, I lugged my bags to the office then I retreated to the cafeteria for coffee. Alesia had given me a good performance evaluation; I’d turned in my files, and said my goodbyes, so there was nothing else to do but wait. I sipped coffee until it was time to report for the shuttle.

At eleven sharp, I stood in the transport office with four others who were scheduled to leave. We were eager to get going, but we were told our flight had been delayed indefinitely because of fighting near the airport.

My thoughts immediately raced to the possibility that the clans were fighting again over jobs. But that wasn’t the case. Nearby street fighting had closed the main road to the airport. Since there was no U.N. involvement security staff informed us as soon as the fighting cleared we’d make a beeline for our flight.

Meanwhile, we had to wait. I knew that flights couldn’t leave for Nairobi after 3 p.m. because there would be no landing space at the Nairobi airport late in the afternoon.

So we had to wait. Every hour that passed, the five of us became more agitated. No one wanted to stay another night in Somalia. We kept pestering the transport officer about our flight, but all he could tell us was to have a seat.

Finally, at 2:30 a security officer reported a lull in the fighting. We had to make a dash to the airport because it could start up at any moment. This would be our last chance of the day. We threw our bags into the bus, and armed security officers loaded into their Nissan Patrols, one in front and one behind us, and we raced to the airport. We arrived at 2:50 and the plane was already warming up on the tarmac.

We tossed our bags into the luggage compartment, climbed in, the door slammed shut, and before we could buckle up the plane taxied to the runway.

Gaining altitude, we flew over the same shot-up airplanes that left such an impression on my first flight into Mogadishu. The destroyed aircraft, on either side of the runway, was a pitiful testament to the endless war that had steadily stripped an already poor nation of so much of its resources, talent, and hope.

Mercifully, as we reached altitude, the tangle of metal below and its inhabitants became indistinguishable, and the mountains of the Kenyan plateau rose abruptly in front of me.

Every Day Death

As I relaxed in my seat, my mind drifted to a conversation I’d had with Ahmad, a Somali kitchen worker. I remember asking him about the war, and in his passable English, he explained how it all began. In the midst of his story, his eyes suddenly grew sad. He said his wife had died recently. She had contracted a sickness that in the past, he could have taken her to a hospital for medicine, and she would have been fine.

But now there was no medicine in any Somalian hospitals because of the war. She died leaving him with two young children.

I didn’t know what to say. I felt angry and sad in the same moment. His wife should never have died like that. I imagined how I would feel if I had lost Chay—devastated, shocked, angry. Finally, I said, “I’m sorry to hear about your wife. What will you do now?”

“Oh, my other wife will take care of them,” he said, shrugging. He then excused himself and returned to his work.

It would be easy to think he was being callous, that this heathen had several wives, so what was the big deal losing one of them, or that he just didn’t value human life as Westerners did. I have heard all of these arguments and maybe some of these do apply in some cases.

But in Somalia, and many places like it, death is a common experience, witnessed first-hand by everyone, children to adults.

Over many years, hundreds of thousands of Somalians died of starvation, hundreds of thousands more died from sickness and disease, and God knows how many died from war and violence. Death of loved ones and friends is as common as birth, probably more so.

Those who allowed the death of someone close to paralyze them ended up unable to function. Where death was so commonplace, it became necessary to adapt to it.

Within the few short months I’d been in Somalia, I’d developed the ability to simply push the tragedy of death down, to not dwell on it, and to go on.

So much of the ability to survive in these difficult assignments and to live in these war-torn countries, depended on one’s innate ability to endure, and to come away from tragedy stronger, ready to help those around us.

There was great doubt that the U.N.’s mission would have a lasting effect on any of Somalia’s pressing problems, but I left Somalia deeply affected by the people and their ability to endure constant tragedy and disappointment.

Little did I know how much I would need every ounce of that ability during my years of peacekeeping…

Don’t forget to leave comments if you want, would love to read them.

Necessary to adapt to death…so difficult to imagine. I look forward to learning more about the ability to endure tragedy. My respect and awe of your life experiences continues to grow.

Holly, thank you for your thoughtful comments, it means a lot to me. I must say that after that first assignment in Somalia I thought hard about whether to continue as a peacekeeper or not. I knew it was a risk not just for me but also for my family, but deep inside I knew it had to be done and I seemed able to do it.

I will try to include some lighter moments in future blogs.

I agree with Holly I am not sure I could adapt to life in that way. I know how precious life is and how fast it can be taken away.

Yes, this experience seems to go against what we are taught about the sanctity of life, but then we do lead a privileged life compared to many, if not most. That is why efforts to improve the lives of people caught in such circumstances is important. Thank you for your comments and thoughts.

i pray that one day it changes. if i could i help but it’s out of my hand . your suffer is all world suffer.